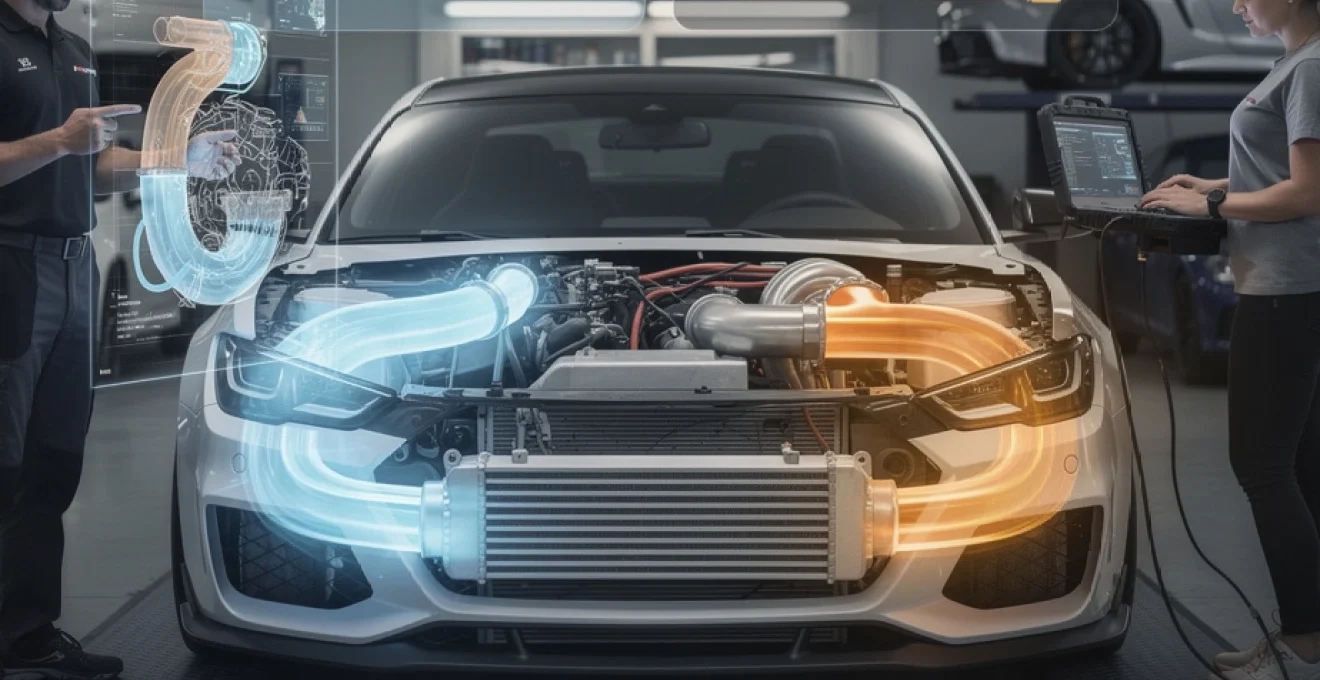

Turbocharged and supercharged engines are everywhere today, from hot hatchbacks to heavy-duty diesels. What allows these compact engines to make big power reliably is not only the turbo itself, but also the way the hot compressed air is cooled before it reaches the cylinders. That job belongs to the intercooler. If you are planning a remap, chasing lower intake air temperatures, or simply trying to understand why modern engines can be both powerful and efficient, understanding intercoolers is essential. Once you grasp how an intercooler manages heat, pressure and airflow, it becomes much easier to choose the right hardware and calibration strategy for your build.

Intercooler basics: definition, thermodynamic role and types in turbocharged engines

An intercooler is a heat exchanger placed between the compressor outlet of a turbocharger or supercharger and the engine intake manifold. Compressed air leaving the compressor can exceed 150–200 °C under high boost; at these temperatures, air density drops and the risk of knock rises sharply. By cooling this charge air, the intercooler increases oxygen density per unit volume, raises volumetric efficiency and stabilises combustion. In practical terms, you gain more power at the same boost pressure, with improved reliability. Although the term “intercooler” is common, some OEMs call it a charge air cooler, especially in diesel and commercial applications.

From a thermodynamic perspective, the intercooler allows the engine to operate at a higher effective pressure ratio for a given knock limit or exhaust temperature. This is why virtually every modern high-boost petrol and diesel engine, whether found in a hatchback or a commercial van, includes some form of charge cooling system. Two broad intercooler types dominate: air-to-air, where ambient airflow cools the charge, and air-to-liquid, where coolant removes heat from the intake air before that heat is rejected to ambient via a secondary radiator. Both designs obey the same physics, but the packaging, cost and response characteristics differ significantly.

Charge air cooling thermodynamics: how an intercooler reduces intake temperatures

Heat exchange principles: conduction, convection and ambient airflow through the intercooler core

The core of an intercooler works in the same basic way as a radiator. Hot compressed air passes through internal passages, while a cooler medium (ambient air or coolant) flows across or around the outside of those passages. Heat moves by conduction through the metal wall, and by convection on both sides of that wall. Aluminium is almost always used because of its high thermal conductivity and low weight. As vehicle speed rises, airflow over the core increases, boosting convective heat transfer and improving cooling efficiency. This is why intake air temperatures often fall dramatically at motorway speeds compared with stop‑start traffic.

In a typical air-to-air intercooler, the compressor outlet may be at 160 °C while ambient temperature is 20 °C. A well‑designed core might cool the charge down to 40–50 °C under sustained load, a temperature drop (ΔT) of more than 100 °C. Motorsport data from recent endurance events shows that for every 10 °C drop in charge temperature, knock margin can improve by around 1–1.5 octane numbers on petrol engines. That improvement translates directly into more timing advance or more boost before the ECU has to pull ignition for knock protection, a critical factor in modern engine downsizing strategies.

Effect on air density, volumetric efficiency and knock resistance in petrol and diesel engines

Why does lowering charge temperature matter so much for performance? The ideal gas law tells you that at a given pressure, colder air is denser. A 100 °C reduction in charge temperature at constant pressure can increase air density by roughly 25–30%. Higher density means more oxygen in the same cylinder volume, which supports more fuel mass and therefore more torque. For turbocharged petrol engines, this density gain combines with reduced knock tendency, enabling more aggressive ignition advance. Knock-limited spark timing can shift by several degrees once intake air temperature (IAT) is brought below 50 °C, especially on engines running 95 RON fuel.

In diesel engines, which operate with excess air and compression ignition, the intercooler still boosts volumetric efficiency and cuts NOx emissions. Cooler, denser air improves mixing and reduces peak combustion temperatures, which in turn helps emissions control hardware like EGR and SCR systems. On both fuel types, a well‑optimised charge air cooling system is crucial for meeting modern Euro 6d and forthcoming Euro 7 regulations, which increasingly tie allowable NOx and particulate emissions to real‑world driving conditions rather than laboratory cycles.

Impact on turbocharger compressor maps, boost pressure and pressure ratio stability

From the turbocharger’s perspective, the intercooler influences where the system operates on the compressor map. Colder intake air at the filter reduces the inlet temperature, while the intercooler controls the outlet temperature seen by the engine. For a given requested manifold pressure, the ECU commands a compressor pressure ratio that must also overcome any pressure drop (ΔP) across the intercooler and pipework. If intercooler restriction is excessive, the turbo has to work harder to hit target boost, pushing operation closer to surge or overspeed zones on the map.

Stable, predictable charge temperatures simplify boost control. When the intercooler keeps IAT consistent across a wide range of ambient conditions, the ECU does not need to vary wastegate duty or variable geometry positions as aggressively to stay within turbine speed or exhaust temperature limits. That stability is particularly helpful in remapped engines running higher boost. Many tuners start by upgrading the intercooler before pushing compressor speed higher, because the extra headroom in knock resistance and turbine duty often yields more reliable gains than simply dialling in more boost on a marginal cooling system.

Intercooler efficiency, temperature drop (ΔT) and pressure drop (ΔP) as key performance metrics

When comparing intercoolers, two numbers matter most: thermal efficiency and pressure drop. Intercooler efficiency is usually defined as the ratio between the actual temperature drop and the maximum theoretical drop if the outlet matched ambient temperature. A street‑friendly front‑mount core might achieve 60–75% efficiency in realistic conditions, while high‑end motorsport charge coolers can exceed 80% under controlled airflow. Pressure drop, by contrast, must be kept as low as practical; values of 0.1–0.3 bar across the core at peak airflow are typical for sensibly sized systems.

These metrics are always in tension. Increasing core size, fin density or internal turbulence improves heat transfer, boosting ΔT and efficiency, but also increases flow restriction and therefore ΔP. A well‑engineered system balances these factors against the turbo’s capabilities and the engine’s airflow demands. For example, data from several aftermarket kits on 2.0 T petrol engines shows IAT reductions of 20–40 °C at sustained 1.4–1.6 bar boost, with pressure drop maintained at or below OEM levels despite higher mass flow, thanks to optimised end tanks and core designs.

Real-world intake air temperature examples: stock VW golf GTI vs tuned subaru WRX STI

Real‑world logs illustrate how dramatically intercooler performance affects IAT. A stock VW Golf GTI (Mk7) with an OEM front‑mounted air-to-air intercooler typically sees IATs around 50–60 °C after a full‑throttle pull in warm weather, starting from about 25 °C ambient. Under repeated pulls, heat soak can push IAT into the 70 °C range, at which point the ECU usually starts to reduce ignition advance and sometimes even boost, cutting power by 5–10%. Aftermarket cores with higher efficiency frequently bring those peak IATs down into the low 40s, preserving timing and power for far longer.

A tuned Subaru WRX STI running higher boost on the factory top‑mount intercooler often shows even more dramatic heat soak. With a hood scoop but limited airflow at low speed, IAT can spike to 80 °C or more after a hard acceleration run on a hot day. Many owners who switch to a well‑sized front‑mount kit report IATs dropping by 25–35 °C under similar conditions, along with noticeably more consistent performance lap after lap. For you as a driver, that translates to stronger pulls, less detuning as temperatures rise, and improved engine longevity due to reduced thermal stress.

Main intercooler designs: air-to-air vs air-to-liquid systems

Air-to-air intercooler layout: front-mount, top-mount and side-mount configurations

Air-to-air intercoolers are the most common solution in both OEM and aftermarket applications. The simplest and generally lightest option, they rely on ambient airflow to cool the charge as it passes through the core. Front‑mount intercoolers (FMIC) sit in the front bumper area, directly in the high‑pressure airstream. This configuration offers excellent cooling potential but often requires longer boost piping and careful packaging to avoid blocking the main radiator. Top‑mount intercoolers (TMIC), used on several boxer‑engine platforms, keep pipe runs short but can suffer from heat soak from the engine and exhaust components.

Side‑mount intercoolers (SMIC) represent a compromise where packaging at the front is limited. Some older performance cars used dual SMICs in the front corners to increase frontal area without a large central core. For a road‑biased build focused on fast road use rather than maximum power, a high‑quality air-to-air intercooler often provides the best balance of cost, simplicity and reliability. When you choose between front‑mount and top‑mount, consider not only peak dyno numbers but also how often the car will sit in traffic or crawl in hot conditions, where top‑mount heat soak becomes far more apparent.

Air-to-liquid intercooler systems: charge coolers, coolant circuits and auxiliary radiators

Air-to-liquid, or charge cooler, systems replace ambient air on the cold side with a dedicated coolant circuit. Hot charge air passes through a compact core mounted close to the engine, where coolant absorbs heat. That heated coolant then flows to an auxiliary radiator, usually at the front of the car, where it sheds heat to ambient. Because water‑glycol mixtures have higher thermal capacity and conductivity than air, these systems can achieve excellent cooling even with relatively small under‑bonnet cores and complex packaging layouts.

Charge coolers shine in applications where space is tight or where radiant heat from the engine bay is severe, such as mid‑engine and rear‑engine platforms. They are also common in high‑end performance cars where consistent IAT control is critical for repeatable performance, such as in track‑oriented models that see sustained full‑load operation. The trade‑offs are additional weight, complexity and cost: pumps, extra plumbing and another radiator must all be integrated without compromising the main engine cooling system. For high‑boost builds, however, the ability to keep IAT within 10–15 °C of ambient even under extreme load can justify this added complexity.

Core construction: tube-and-fin vs bar-and-plate design, fin density and flow characteristics

The internal construction of an intercooler core strongly influences both cooling performance and pressure drop. The two main architectures are tube-and-fin and bar-and-plate. Tube‑and‑fin cores are often lighter and less restrictive, using thin extruded tubes with attached fins. They tend to heat up and cool down quickly, which can be beneficial for short bursts, but may be more prone to heat soak under long, high‑load periods. Bar‑and‑plate designs use solid bars and thicker plates, offering higher strength and generally better heat rejection per unit frontal area at the cost of extra mass.

Fin density and internal turbulence structures also matter. Higher fin density and more aggressive internal turbulators increase the internal surface area for heat transfer, raising efficiency but also increasing flow resistance. External fin design must balance cooling airflow with the need to avoid excessive blockage of the main radiator behind the intercooler. When choosing a core for a high‑boost build, you should consider both the expected mass flow and the desired IAT target. Oversizing the core without regard to flow characteristics can lead to unnecessary turbo effort and more turbo lag, especially noticeable in road cars driven daily.

OEM solutions vs aftermarket performance kits from brands like mishimoto, wagner tuning and forge

Original equipment (OEM) intercoolers are designed around strict cost, weight and packaging constraints. For stock power levels and typical duty cycles, they are usually adequate, but many start to struggle once you push 30–50% above factory output. Aftermarket performance kits from specialist brands are engineered to deliver lower IATs and reduced pressure drop at higher flow rates, often using bar‑and‑plate cores, cast end tanks and optimised internal geometries. It is common to see dyno tests where a quality aftermarket intercooler unlocks 10–20 bhp on a remapped turbo engine simply by allowing the ECU to hold target boost and timing for longer.

From a professional perspective, one of the most overlooked benefits of a high‑performance intercooler is consistency rather than peak power. Many tuners observe that with an upgraded core, power on the third or fourth pull is almost identical to the first, whereas the stock system may lose 5–15% as it heat soaks. For you as an enthusiast, this means more predictable performance on track days, repeated launches that feel the same, and less risk of the ECU pulling power aggressively on a hot summer afternoon when intake temperatures would otherwise spiral.

Use cases: road cars, endurance racing, drag racing and circuit applications compared

Intercooler design priorities shift depending on how the vehicle is used. Daily‑driven road cars favour moderate core sizes, good low‑speed airflow and minimal turbo lag. Heat soak over hours of mixed driving matters more than absolute peak cooling for a single run. In endurance racing, the system must survive sustained full‑load operation for hours; here, large frontal area, high‑efficiency cores and robust ducting are essential. Teams often accept a small pressure drop penalty to achieve IAT stability across an entire stint, as consistent power is more important than the last few horsepower.

Drag racing and roll‑racing builds, by contrast, prioritise short‑term cooling for extreme boost levels. Oversized front‑mount cores with high fin density are common, and some setups even use water‑spray or ice‑water reservoirs in air‑to‑liquid systems to achieve intake temperatures below ambient during a pass. Circuit and time‑attack cars fall somewhere between endurance and sprint setups; they need serious cooling for multiple laps, but packaging and aero efficiency become crucial. In that context, careful integration of the intercooler with front splitters, air dams and under‑tray designs can deliver both strong cooling and stable high‑speed balance.

Intercooler placement and packaging in modern vehicles

Placement of the intercooler within the vehicle heavily influences both effectiveness and side‑effects like turbo lag and radiator performance. Mounting the core at the very front maximises ram air cooling, but every centimetre of added piping between compressor and throttle body increases internal volume and therefore the amount of air that must be pressurised before boost reaches the cylinders. On transverse hot hatches, manufacturers often integrate the intercooler within a multi‑layer front stack including condenser and radiator, trading some efficiency for reduced pipe length and simpler assembly.

Packaging constraints are even more severe on downsized turbo engines in compact platforms. Designers must avoid creating “shadowed” areas where airflow is blocked by crash structures or styling elements, because stagnant air zones can reduce effective cooling area by 20–30% according to wind‑tunnel data published at recent OEM engineering conferences. For you, this means that fitting a much larger aftermarket intercooler behind a largely closed grille without additional ducting may reduce gains versus a smaller, better‑fed core. Carefully shaped shrouds and inlets often make more difference than another 10–20 mm of core thickness.

Pressure drop, turbo lag and airflow management through the intercooler system

Boost piping routing, internal turbulence and their influence on throttle response

The layout of boost pipes from turbo to intercooler and on to the throttle body or intake plenum affects both steady‑state pressure drop and transient response. Sharp bends, sudden diameter changes and rough internal surfaces all create turbulence, which raises resistance and can contribute to audible whistles or whooshes under boost. Long pipe runs increase total internal volume, which slightly delays the time it takes for pressure to build when you step on the throttle, perceived as extra turbo lag. In a responsive road car, those small delays can make the car feel less eager, even if peak power has increased.

From a tuning standpoint, a smart upgrade path involves not only a more efficient intercooler core but also tidier, smoother piping. Mandrel‑bent aluminium or stainless tubes with gentle radius bends and minimal couplers reduce the number of potential leak points and lower flow losses. Keeping internal diameters matched to expected flow helps maintain air velocity and response. If you are chasing sharper throttle response for fast road driving, prioritising a clean, compact piping layout may yield more daily enjoyment than the largest possible core squeezed into the bumper.

Calculating and minimising intercooler pressure losses for high-boost builds

For high‑boost or high‑flow builds, estimating intercooler pressure drop becomes critical. Pressure loss depends on air density, flow velocity, core geometry and surface roughness. Many serious tuners use flow bench data or manufacturer‑supplied pressure‑flow curves expressed as ΔP vs mass flow rate. As a rule of thumb, for a 300–400 bhp four‑cylinder running 1.5–2.0 bar of boost, aiming for less than 0.2–0.25 bar pressure drop across the entire charge air system (intercooler plus piping) is a sensible target. Beyond that, the turbo must work significantly harder, generating more heat and raising turbine shaft speeds.

To minimise losses, focus on three areas: appropriate core sizing, efficient end tank design, and smooth transitions in pipework. Overly small cores force higher velocities, increasing frictional losses, while oversized but poorly designed cores can generate internal recirculation zones that add restriction without much cooling benefit. Well‑shaped end tanks with gradual tapers and internal diverters help distribute flow evenly across the core face, improving both ΔT and ΔP. For you, the practical advice is to choose proven designs with published data rather than guessing based on external size alone.

Turbo lag trade-offs: larger core volume vs transient boost response in road vs track cars

Any increase in system volume between the compressor and intake valves adds some delay to boost build‑up when you open the throttle. In many cases, this added lag is small—often a few tens of milliseconds—but sensitive drivers notice it, especially in lower gears. A massive front‑mount intercooler with long pipe runs might be perfect for a drag car that lives at high load, yet feel slightly dull at partial throttle in city driving. The trade‑off between charge cooling and response is one of the key decisions when specifying an intercooler for a dual‑purpose road and track car.

One effective strategy is to size the intercooler just above the expected power level, rather than overspecifying dramatically. Another is to combine modestly larger cores with careful ECU calibration, adjusting boost control and throttle mapping to compensate. Modern engine management systems can ramp wastegate duty or variable geometry vanes more aggressively at low rpm to offset small increases in volume. If you value sharp response more than peak dyno numbers, choosing a slightly smaller but efficient core, paired with tuned boost control, usually provides a better driving experience.

Shroud design, ducting and splitter use to optimise ram air to the intercooler face

Intercooler performance depends heavily on effective airflow across the external fins. Shrouds, ducts and under‑tray designs direct high‑pressure air to the core face and encourage smooth exit flow, preventing hot air recirculation in the engine bay. A well‑sealed shroud between the bumper opening and intercooler ensures that most of the air entering the grille passes through the core rather than around it. Similarly, vents in the under‑tray or bonnet can reduce pressure behind the radiator and intercooler stack, promoting stronger mass flow at speed.

For track‑focused cars with front splitters, the pressure distribution around the front of the vehicle changes significantly. The splitter can create a low‑pressure area under the car that helps draw air through the cooling stack. CFD studies presented at recent motorsport engineering conferences show that optimised ducting and splitter integration can increase effective cooling air mass flow by 10–20% without enlarging the grille opening, reducing drag and improving both cooling and high‑speed stability. Even on a fast road build, simple additions like foam sealing strips and tailored plastic ducts can yield surprisingly large reductions in IAT.

Case studies: OEM airflow strategies on BMW M3, audi RS3 and nissan GT‑R intercooler systems

Modern performance cars offer instructive examples of advanced intercooler packaging. Recent BMW M3 models with turbocharged inline‑six engines use an air‑to‑water charge cooler mounted on top of the engine, with a dedicated low‑temperature radiator in the front bumper. This layout shortens the charge path and improves response while relying on the auxiliary coolant circuit to maintain low IATs during hard use. The design demonstrates how OEMs use charge cooling to reconcile emissions, packaging and performance targets in compact engine bays.

The Audi RS3 employs a large air‑to‑air intercooler integrated into the front bumper, fed by carefully shaped ducts and supported by under‑tray airflow management. Log data from track users often shows stable IATs in the 40–50 °C range even with stage‑one remaps, highlighting the strength of the OEM design. The Nissan GT‑R, with its twin‑turbo V6, uses twin side‑mounted intercoolers positioned to balance cooling performance and minimum piping length. The GT‑R’s intercooler package underlines how, at higher power levels, symmetry and balanced airflow to each bank of cylinders become crucial for knock control and consistent cylinder‑to‑cylinder performance.

Intercoolers in ECU calibration, knock control and emissions strategies

In modern engine management, the intercooler is tightly integrated into ECU strategies for knock control, torque delivery and emissions. Intake air temperature sensors placed after the intercooler feed real‑time data to ignition, fuel and boost maps. When IAT rises above calibrated thresholds—often around 50–60 °C on performance petrol engines—the ECU reduces ignition advance, enriches mixtures slightly and may lower boost to protect the engine. These interventions preserve durability but cost power and efficiency, which is why a more capable intercooler often yields substantial gains even at unchanged peak boost levels.

For emissions, stable charge temperatures simplify combustion control. On direct‑injection petrol engines, precise temperature management reduces particulate formation and helps three‑way catalysts operate within optimal windows. In diesels, consistent IAT supports accurate control of EGR rates and limits NOx formation by preventing excessive combustion temperatures. In personal experience, calibrations on engines with marginal stock intercoolers often require conservative timing and boost at high ambient temperatures to pass real‑driving emissions tests, whereas the same engine with improved charge cooling can maintain closer‑to‑ideal maps across a much broader climate range.

Intercooler selection, sizing and upgrades for remapped and high-boost engines

Choosing the right intercooler for a remapped or high‑boost engine starts with clear power and usage targets. For modest stage‑one tunes on daily‑driven cars, a direct‑fit, slightly higher‑capacity air‑to‑air intercooler that preserves OEM mounting points and uses sensible pipe diameters usually offers the best value. Look for data showing IAT reductions—ideally at least 15–20 °C under sustained load—alongside acceptable pressure drop figures. Core dimensions should be chosen to fit available frontal area without fully blocking the radiator or requiring extensive cutting of crash structures, which can compromise safety and insurance acceptance.

For more serious builds aiming at 50–100% power increases, more systematic sizing is recommended. Estimate expected mass airflow based on power targets (a rough guide is around 0.17–0.2 kg/s air per 100 bhp on petrol engines) and select a core rated comfortably above that flow at your intended boost pressure. Consider whether an air‑to‑liquid system might better suit your packaging if space in front of the radiator is limited. Pay attention to supporting hardware: high‑quality silicone couplers, reinforced clamps and properly routed hard pipes all contribute to reliability. Finally, ensure that the ECU calibration is updated to reflect the new intercooler’s behaviour, especially if IAT dynamics change significantly; this allows you to exploit the improved knock margin safely and achieve the full benefit of the hardware upgrade.